The Gifts in Making: Dyani White Hawk

Three American artists explain what the notion of the gift means to them, how it shapes their work, and what memorable gifts they’ve received.

As published in American Craft Council, Tuesday, December 8, 2020.

This article also appears in the December/January 2021 issue of American Craft Magazine.

↑ Dyani White Hawk (Sičáŋǧu Lakota) is a visual artist and independent curator based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Photo: Courtesy of Dyani White Hawk

ART OF CONTRIBUTION

Minneapolis-based artist Dyani White Hawk considered the concept of the gift in all its complexity while she was preparing for her 2020 exhibition “She Gives” at the Plains Art Museum in Fargo, North Dakota. The title of her exhibition comes from a series of paintings called Quiet Strength. Three of the works in this series are titled She Gives (Quiet Strength). Here, the word “she” refers to the land, which White Hawk says “sustains us, carries us, and gives us everything we need,” to Indigenous women, whose art and contributions have long been left out of mainstream cultural narratives, and to all women.

“Generosity and reciprocity are core Lakota values ingrained in who we are, and they guide our definition of how we practice being good relatives,” says White Hawk, who grew up in Madison, Wisconsin, and was raised primarily by her mom, who is Sičáŋǧu Lakota. These values around giving have shaped White Hawk as a person and as an artist whose work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Denver Art Museum, Minneapolis Institute of Art, and Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

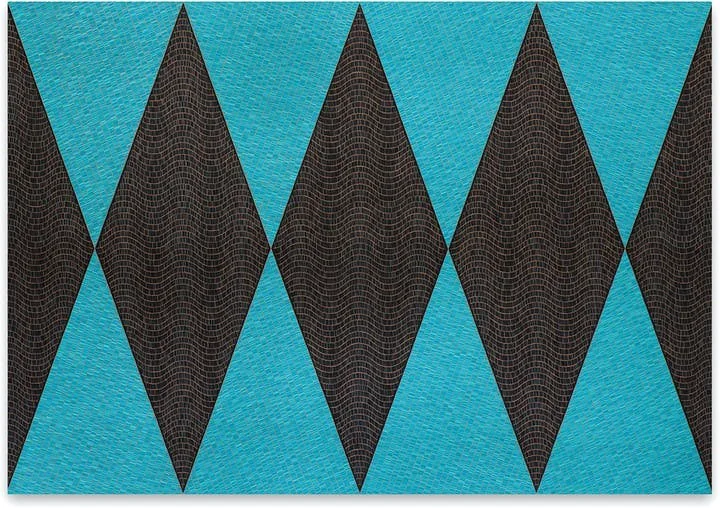

She Gives (Quiet Strength VII) is part of Dyani White Hawk’s Quiet Strength series of paintings. “She” refers to the land, Indigenous women, and all women. Photos: Courtesy of Dyani White Hawk

Her path hasn’t been easy, though. Coming to a contemporary art career through an academic MFA program, White Hawk had to grapple with the capitalist realities of the art market, knowing that if she wanted to make work that would be widely shown, seen, and reviewed – to have her voice added to an art world canon that has historically excluded the work of Indigenous people – she would need to negotiate the values of the art world with her cultural values. That has required holding two kinds of practice in tandem: creating works for the market and creating works for personal and familial use.

White Hawk identifies primarily as a painter, characterizing painting as “the root” of her studio practice. But she’s inspired by and employs multiple artistic histories and mediums. “I do a lot of work for cultural reasons, like beadwork, quill work, and sewing,” she says, noting that in Native communities, beaded and sewn objects – as well as articles of clothing – are used for ceremony and social gatherings. “Those works, such as moccasins and dresses, are for cultural practices, not for the gallery or museum. But the work in each space informs one another.”

“Everything I do,” White Hawk says, “comes from gifts that have come down from generations of people who sustained those practices before me. These gifts have been passed down for far longer than we can document.”

Made from buckskin, synthetic sinew, thread, glass beads, brass sequins, and a copper vessel and ladle, Carry II (2019) is the second piece in White Hawk’s Carry series. White Hawk says the series consists of functional works that critique discriminatory hierarchies that have “othered” work by Native artists, while encouraging careful consideration of what Native artists choose to carry forward. Photos: Courtesy of Dyani White Hawk

These gifts go beyond aspects of making. Her practice is guided by “gifts in the form of cultural teachings that aren’t specific to artistic production,” she says. “My perspective on life, on making, on creation, on how I want to move through the world – all of that is a by-product of being raised as a Lakota woman. I really think of my entire practice as a gift from those who have gone before me, including all the practitioners of easel painting, too. This gift is all-encompassing. None of it is my creation or invention.”

The actual process of making, White Hawk says, gives her a most precious gift: “My sanity. I’ve learned that when I’m not making, I’m not my happiest self, my best situated or most emotionally stable self. Making gives me the greatest sense of fulfillment, joy, intrigue. It gives me time to be contemplative and inquisitive. In a lot of ways, it gives me my life force.”

“Everything I do comes from gifts that have come down from generations of people who sustained those practices before me. These gifts have been passed down for far longer than we can document.”

~Dyani White Hawk

Photo: Courtesy of Dyani White Hawk

White Hawk says we’re all born with particular gifts, things that are inherent in us, our life’s calling. “Following that and listening to that is how we contribute to our world,” she says. “There’s a lot of pain and trauma in our Native communities that endures from colonization to this day. My art is a way that I can contribute to the health and well-being of our people. The vast majority of Native folks can’t walk into a museum and see Native artists. We deserve to have that – that joy you feel when you have an exchange with a work of art that speaks to your life experience.”