Global Cottage Industry

Artistic endeavors with women weavers from North Africa and the Middle East

As published in Hand/Eye Magazine on September 26, 2012

The Middle East has long been synonymous with masterful craftsmanship: architecture, ceramics, textiles, carved wood, manuscripts and metalwork dazzle museum-goers and tourists alike, and inspire designers and artists all over the world. In the traditional cultures of this storied region, women still play a secondary role as artisans, says designer, entrepreneur and global traveler Tucker Robbins. Currently working with the Abu Dhabi Authority of Culture and Heritage, Robbins had the insight that collaboration among cultures within the Islamic world is critical to developing a network of craftswomen powerful enough to open the doors to economic and artistic possibilities.

After four trips between the Tunisian Sahara in North Africa and Abu Dhabi in the Persian Gulf, Robbins has connected women weavers from these two regions who are now collaborating on a large encampment of woven components arranged to create quarters for the Minister’s guests. With any luck, it will be the first project of a new collaboration that helps draw attention to the value of these artists’ practice. The Bedouin women of Tunisia are exchanging their techniques with Abu Dhabi's women as part of the Abu Dhabi's Ministry of Culture’s Handicrafts Project. “The courageous women exchanged skills, stories, and trade secrets, along with food and tea from their home lands,” Robbins writes. Robbins does not speak Arabic and the weavers do not speak English, but they have developed a lingua franca all their own through what Robbins calls “the graphic language of weaving”—a universal dialogue bound up with history, design, process and humanity.

The connection is more than an artistic one: the goal of the program is to protect the practice of traditional crafts and to support the cottage industries that so often provide crucial income for women who create goods in small home workshops. Supplies are expensive, techniques must be taught carefully, and both advertising and sales can be daunting in a complex global marketplace. The Handicrafts Project offers support in all areas of production and trade so that the artistic livelihood of these talented women can find eager buyers and widespread appreciation in the region for their role in preserving their countries’ cultural heritage.

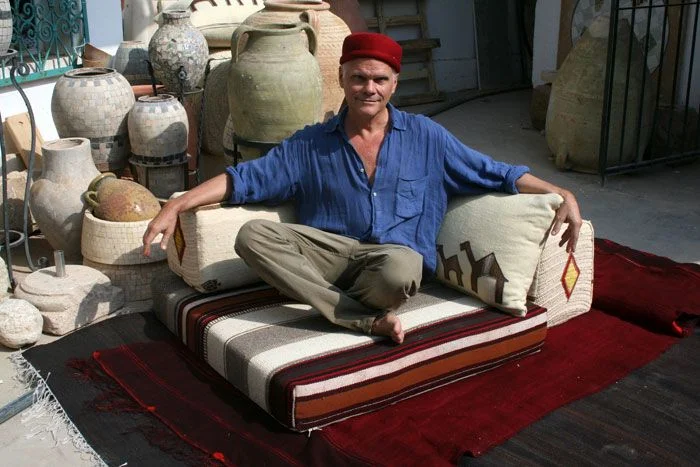

Robbins’ role in this endeavor is part ambassador, part artistic muse. A veteran of the design world who lives New York City, he has been traveling the globe for years to study the patterns and forms of crafts from South America to the South Pacific. He designs furniture and sustainably sources exotic woods from remote tropical regions, working with local artisans to help create his designs. Because it is against the law to harvest some of the rare species of exotic hardwoods he favors, he often “up-cycles,” buying timber that has already been cut down—some of it even incorporated into houses. Old floorboards become side tables, the curve of a tree root lends a design element to a new chair, an old basket made from plant fiber is given new life as a lamp.

You’d never guess that this connoisseur of well-crafted goods lived an utterly Spartan existence as a monk for nearly 10 years, during which he was focused on the spiritual world, and the material world took a back seat. But for Robbins, the making and selling of goods is not mere business. It is a system that makes it possible for men and women across countries and cultures to thrive doing something that embodies their values and cultural heritage, gives joy to those who live with their creations, and his ethical approach to sourcing raw materials is a model for sustainable designers everywhere. Desirable products, social mobility for women in developing countries, and the protection of natural resources can coexist fruitfully if the right mechanisms are in place to make it happen. The “sameness” of goods on the commercial design market doesn’t interest him: symmetry, repetition, monotony are fine for some, but in his efforts to support artisans around the world, Robbins eschews perfection in favor of something even better: harmony.

For more, see www.tuckerrobbins.com.