Photographs from a 1950s Cross-Dressing Retreat

Photographs from the Casa Susanna collection (all images courtesy Wright)

An elegant black envelope arrived in my mailbox last week. Inside is a square, burgundy-colored folder containing a catalogue of 1950 and ’60s snapshots. On the cover, an off-white, hand-lettered logo reads “Casa Susanna.” The photographs reproduced inside appear at first glance to portray a group of women at leisure: posing in the kitchen, dressed smartly for dinner, sporting fashionable bathing suits, sitting in a field of wildflowers. They are to be sold as a single lot by Wright auction house on October 30.

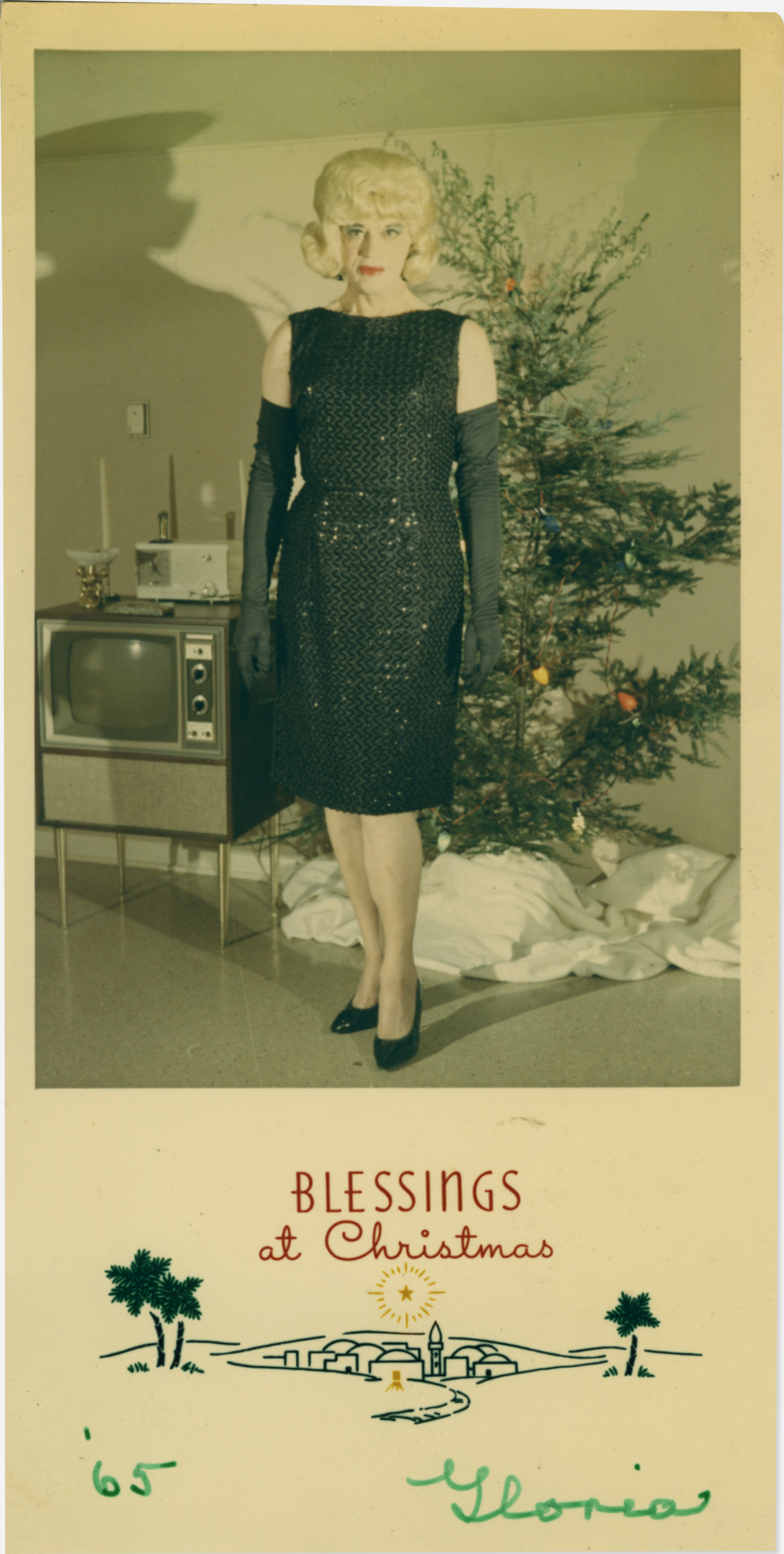

In keeping with Wright’s focus on postwar American design, the Casa Susanna pictures depict a world of bouffant hairdos, transistor radios, pillbox hats, and mink coats. Middle-of-the-line midcentury furniture can be seen in many of the images, sporting tweedy upholstery and tapered legs. Yet the subjects’ bodies are taller, broader, and squarer than you might expect, especially in the era of the nipped-in waist. That’s because all of the people in the photographs are men. Interestingly, the gender norms are of the same vintage as the clothing and décor, though; instead of fluidity or ambiguity, we see a kind of certainty and clarity. Dressed as they are in ordinary, even conservative women’s attire, these men look ready to host a game of bridge or bring a PTA meeting to order. Who are these subjects? Where is this place? And how did their photographs end up at an auction house known for pioneering the secondary market for postwar design?

The story begins, as so many good ones do, at Manhattan’s West 26th Street flea market. Robert Swope and Michel Hurst, the proprietors of Full House, an antiques gallery specializing in mid-century wares, discovered a suitcase containing 340 photographs that documented the life of a summer retreat in Hunter, NY, called Casa Susanna. Immediately intrigued, they brought the suitcase home and began studying the images inside. Though they generally deal in furniture, not photography, this particular find seemed to fit right into the logic of their flea market sleuthing habits. “Our interest in the collection overlaps with our professional activities as both are about unearthing interesting objects and artifacts from recent history,” Swope told Hyperallergic via email. “It is about the rediscovery of what mattered in a certain period, be it a chair, a lamp, or the expression of a marginal group in society.”

The resort took its name from its proprietor, Susanna, who, when not at the camp, was known as Tito Valenti. Valenti’s wife, Marie, ran a wig shop in New York City. From the mid-1950s through the early 1960s, a group of heterosexual men, many of them married with families, spent weekends at Casa Susanna dressed in feminine finery. And though they kept their activities under wraps, they clearly delighted in documenting their time there, perhaps because the photographs made something in their experience tangible and real.

Indeed, the realness of the pictures gives them a tender sort of innocence: they are not remotely sexualized or “naughty,” but sweet and domestic. “The fact that it is not sexual is a great part of the interest,” says Swope. “It signals that these photos are talking about something else more mysterious and important. An audience in the ’60s would never have seen these photos — they were never meant to be seen by anyone outside of the group. They were private and dangerous. In 2014 a large audience is open to learn about and explore all sorts of diverse identities. The phenomenon of cross-dressing and gender identification — as old as the world — is as relevant today as it has always been, and its discussion more openly so.”

It’s intriguing to speculate who these men were, where they ended up, if they knew what ever became of these photographs (why didn’t they keep them?), and what, if anything, became of this community. Did they keep in touch? Did they wonder about one another over the decades? The fact that the collection is largely anonymous, and that the images play to archetypes of femininity, give the photographs a hint of the work of Cindy Sherman, William Eggleston, or Diane Arbus. Because of its historical import, says Richard Wright, he, Swope, and Hurst felt it was critical to keep the photographs together instead of breaking them up into individual lots. This will make them more challenging to sell, but will ensure that the world they document will remain, to some extent, intact. Whether a private collector or an institution decides to bring Casa Susanna home will be determined on October 30, when the photographs’ next chapter will begin.

Casa Susanna: A Photographic Archive will be auctioned at Wright on October 30. A book about the collection, edited by Hurst and Swope, is also available from Amazon and other online booksellers.