How Dutch Wax Fabrics Became a Mainstay of African Fashion

The Philadelphia Museum of Art examines the past and present of Vlisco fabrics, a symbol of our hyperconnected, postcolonial material world.

As published in Hyperallergic on November 3, 2016

Installation view, Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (photo by Tim Tiebout, courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

PHILADELPHIA — Riotously colorful, densely patterned, and unassailably fabulous, Vlisco fabrics have, for decades, been tailored into shift dresses, power suits, and formal gowns for Central and West Africa’s cosmopolitan elite. Their patterns and palettes evince an instantly recognizable aesthetic. And there are scores of Vlisco imitators: Chinese knockoffs are sold on city streets all over the world. But are any of these fabrics in fact African? The exhibition Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage, on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) as part of a suite of shows and programs called “Creative Africa,” poses this question in an indirect but intriguing way, by explaining the company’s origins in the Dutch colonial empire and demonstrating its products’ lasting popularity, in African fashion and beyond. Art enthusiasts, for instance, might recognize Vlisco fabrics from the work of Yinka Shonibare MBE, who has used the them to fashion Victorian-style gowns and waistcoats for the generally headless human figures in his haunting installations. In Shonibare’s work, the fabrics do conceptual double duty: they act as a symbol of “African culture,” for those who perceive their patterns to be indigenous, and as a symbol of our hyperconnected, postcolonial material world, for those who understand the complexities of their origins.

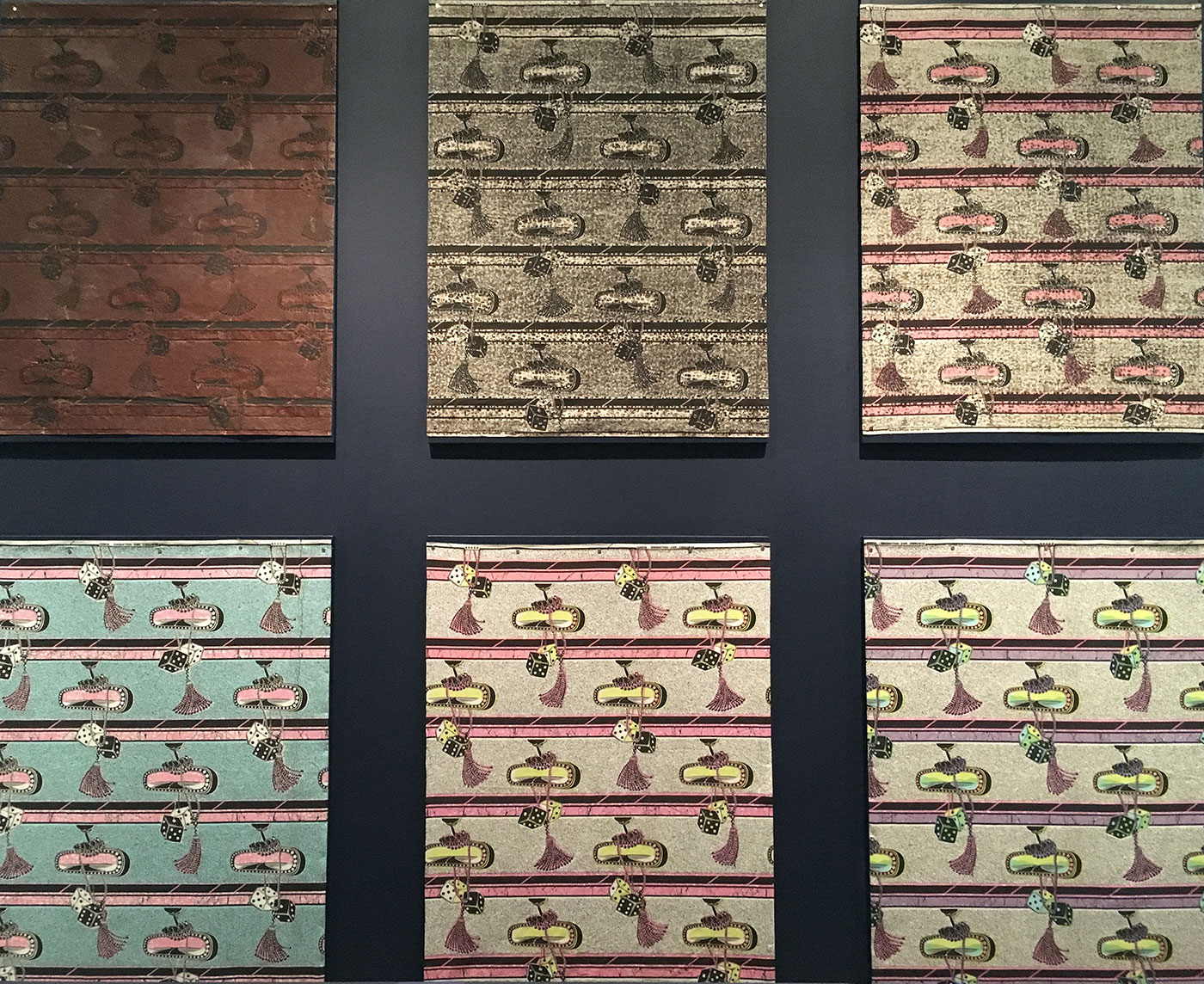

Textile pattern by Constance Girard for Vlisco on view in Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The story of Vlisco begins not in Dakar, Lagos, or Accra, but in the small Dutch city of Helmond, where, in 1846, industrialist Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen purchased a textile factory with the goal of selling upholstery fabric, bedspreads, and handkerchiefs abroad. Van Vlissingen began creating imitation batik fabric based on designs from Indonesia — then known as the Dutch East Indies — with the goal of capitalizing on new roller printing technology that could effect the look of batik without all the labor-intensive work required to make the real thing. Batik originated in China and India in the 8th century, and it was refined in 13th-century Indonesia with the development of a new tool for applying hot wax to fabric known as canting, likely an anglicized form of the word tjanting. When Dutch imitators such as van Vlissingen entered the business, Indonesians noticed small flaws in their fabrics — namely a “crackle” effect, the result of small veins of pigment leaking through the wax resist — and the Dutch East Indies even went so far as to ban their sale in the 19th century. But other areas of the Dutch empire provided a ready, if unexpected, marketplace. Vlisco fabrics became a popular item in a different part of the Dutch colonial ecosystem, starting in Ghana, which was then called the Gold Coast.

Between 1855 and 1872, approximately 3,000 Ghanian soldiers served in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army. They returned home, as servicemen often do, with a taste for items they encountered abroad. As the story goes, the soldiers had learned to appreciate the look of genuine batik but didn’t mind the crackle of the van Vlissingen version, so they purchased bolts of it for their female relatives back in Ghana. By the turn of the century, despite the ceding of the colony to the UK, the sale of Dutch-made faux batik in the Gold Coast was robust. By the 1930s, it was being adapted to suit Ghanian tastes, not by accident, but by design. According to Dilys Blum, the PMA’s senior curator of costume and textiles who organized the exhibition, the trend was so popular that several companies based in England, France, and Switzerland began producing faux batik fabrics in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Van Vlissingen responded by consolidating its grip on the marketplace and buying up several smaller concerns. Thus, a fabric produced in Europe with Asia in mind never quite hit the mark in its intended marketplace, but found an enthusiastic audience at the opposite end of the empire.

The Vlisco factory in the 1950s–60s (image courtesy Vlisco)

The Vlisco factory in the 1950s–60s (image courtesy Vlisco)

Garments made with Vlisco fabrics. From left to right: Pepita D, Gala Dress (2016), cotton, Java print, sequins; Josephine Memel, Gala Dress (2016), cotton; wax block print; Lanre da Silva Ajayi for Vlisco, Gala Dress, Splendeur collection, season 4 (2014), cotton, wax block print (photo by Tim Tiebout, courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

In 1927, the company adopted the more modern name of Vlisco. Terms such as “Dutch Wax,” “Veritable Dutch Hollandais,” and “Wax Hollandais” were also commonly used for Vlisco fabrics, but branding became more important when World War II temporarily halted production in the Netherlands. Imitators sprang into action, producing knockoffs for the West African market. In the years following the war, purveyors of Vlisco fabrics became increasingly concerned with authenticity and protecting their business from the ersatz textiles (a slightly ironic phenomenon, given the company’s origin as an imitator itself). Since 1963, Vlisco fabrics have been stamped with the phrase “Guaranteed Dutch Wax Vlisco” on every selvage, making proof of authenticity an important aspect of the product’s allure.

Today, the Vlisco Group has four brands: Vlisco, Woodin, Uniwax, and GTP (Ghana Textiles Printing Company). The latter three are produced in parts of Africa, and all four market their slightly different designs to slightly different segments of that continent’s marketplace. To this day, Vlisco’s precise mode of production remains a trade secret, with 27 distinct steps carried out by both machine and hand. But as Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage makes clear with a short video and examples of pattern blocks, there are aspects of the fabric’s production that are quite traditional and remain rooted in the indigo resist technique that van Vlissingen first adapted to industry.

As fascinating as the mysteries of production are for textile nerds, the stars of this exhibition are the fashions and patterns themselves. While the aesthetic of Vlisco still evokes batik to this day, the patterns are full of culturally specific references and visual cues that communicate ideas and sentiments in the largely female world of its sellers and consumers. While Vlisco uses only stock numbers to identify its patterns, traders and buyers have invested many of them with narratives, and some have become iconic. The pattern known as “You Fly, I Fly,” which depicts a bird escaping from a cage, is a favorite of newlywed women, who wear it to advertise that faithfulness in marriage is a two-way street. In Togo, the Vlisco trade is controlled by a small group of families who have state-issued licenses, which are passed down from mother to daughter. One pattern known as “Mama Benz” depicts that recognizable hood ornament in commemoration of the first Mercedes purchased by a member of one of Togo’s leading trader families. Blum argues — and it’s hard to disagree — that this complex dynamic is what makes Vlisco such a fascinating phenomenon of material culture: it represents an economy in which a global brand’s significance can actually be hyperlocal.

Blocks used in the process of making a Vlisco printed textile, on view in Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Textile patterns in Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage, with the Mama Benz pattern by Christof Zürn for Vlisco in upper right (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Vlisco’s patterns are created at the company’s headquarters in Helmond by a team of designers who hail from various parts of Europe and Africa. At the PMA, swatches of those fabrics surround a catwalk of looks that make gorgeous use of them, in garments ranging from Courreges-like shift dresses to curvy gowns with peplums and ruffles. The show also includes the work of Philadelphia-based designer Walé Oyéjidé, who uses Vlisco-inspired fabrics in his lines for menswear company Ikiré Jones, where he is the creative director.

Vlisco’s relationship with high fashion is complex. According to a 2012 article in Slate by Julia Felsenthal, the designer Junya Watanabe used some Vlisco patterns printed on silk in a 2009 runway show for Comme des Garçons; after the company told him to stop, Watanabe and Vlisco reportedly settled the matter amicably. What’s revealing about the incident, however, is that it might not have occurred to Watanabe that he was plagiarizing, because people outside of Africa often fail to understand and credit the creative authorship coming from its myriad and very distinct regions. Jessica Helbach, a designer from the Netherlands whose studio has collaborated with Vlisco, told Felsenthal, “When people think things come out of Africa, they don’t worry about copyright.” With Vlisco’s rising profile in the fashion world, this may be changing. But it’s also plausible that the label of “African fabric,” like “African art,” flatten outs and simplifies its contents, attributing design, production, and consumption to anonymous craftsmen and buyers rather than makers and consumers with personal tastes and points of view.

Installation view, Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (photo by Tim Tiebout, courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Patterns designed by Inge van Lierop for Vlisco. From left to right: dress, Bloom collection, season 2 (2014); dress, Bright and Beautiful collection, season 2 (2016); ensemble, Fantasia collection, season 3 (2014); dress, Bloom collection, season 2 (2014); all cotton and wax block prints (photo by Tim Tiebout, courtesy the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

To some extent, the question of whether Vlisco is truly “African” or not is moot, because the fabric so readily and indelibly signifies the fashion and style of West African women; it might be like asking if denim is “really American” given the complex global history of indigo. At this point, Vlisco is about much more than just the fabric as an object of fashion. The ecosystem and visual language of its trade is a cultural phenomenon in which women entrepreneurs flourish, and individuals can forge and display their identities through design.

One of the masterstrokes of this small but rich exhibition is that, wherever possible, the designers of each pattern are credited near their fabric samples, and each dress or suit is likewise attributed. Some are of West African descent, some Northern European. All are bracingly original.

Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage continues at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Perelman Building, 2525 Pennsylvania Avenue) through January 22, 2017.