Lessons from Utopia

As published in American Craft, October/November, 2020

What tools and resources do communities need to live apart from the rest of society? How might their crafts manifest their ideals or support their utopian endeavors?

IN 1516, THE PHILOSOPHER and statesman Sir Thomas More introduced a new word to the English language when he published his book Utopia, describing a fictional ideal society on an island in the Atlantic Ocean. Derived from the Greek words ou (“no” or “not”) and topos (“place”), utopia literally means “not a place.”

Though the utopian communities that have been created since the word was coined – from 19th-century groups to hippie communes – have been rich with idealism and hope, the fact that utopia can also be translated as “nowhere” makes it seem as though the failure of most intentional communities is subtly built into the word that describes them. If you followed the ill-fated story of Biosphere 2 in the 1990s, or, more recently, listened to the Curbed podcast Nice Try!, you know that utopias have a way of going under. Two of the most significant American utopian societies, the Oneida Community and the Shakers, eventually followed that downward arc. But both have left a legacy of craft that’s as alive today as it ever was. What lessons do they hold for maker communities in America today?

Craft and Utopia

Utopian communities have often emphasized crafts, because many groups who choose to live apart from mainstream society do so in an effort to escape factory work, mass production, and capitalism. So what tools and resources do communities need to live apart from the rest of society? How might their crafts manifest their ideals or support their utopian endeavors? Certainly the ability to grow and cook food, build shelter, and make clothes is a necessity, but what about crafting goods that people outside the community might want to buy? For numerous intentional communities formed in the 18th and 19th centuries, the production of goods aimed at consumers in mainstream society was part of the economic formula that helped them to live apart.

You might associate the name “Oneida” with silverware, and you probably know that Shaker furniture and wares are among the most outstanding examples of American craftsmanship. But you might not know the complex stories of the communities that produced these beautiful things.

Both communities were affected by a Protestant religious revival called the Second Great Awakening, which emerged in the 1790s predominantly among Methodists and Baptists in Kentucky and Tennessee and spread outward during the early 19th century. Denominations within the movement placed emphasis on making a personal connection with God, free of church or minister. The Oneida Community went even further, practicing a form of nonmonogamous relationships called “complex marriage,” while the Shakers eschewed marriage and partnership altogether. Both communities believed that children should be raised communally.

All of this may come as a surprise if you’re used to seeing Oneida silverware and Shaker furniture sold as adjuncts to an ideal of cozy nuclear-family life; yet the legacy of these radical communities lives on significantly in the objects they produced.

The Shakers: Celibate and Ecstatic

The Shakers, a breakaway sect of Quakers whose official name is the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, have been described as “millenarian nontrinitarian restorationist” Christians, which means that they anticipated the coming of a fundamental transformation of society, they rejected the concept of the Holy Trinity, and they sought to return to what they saw as an unalloyed, ancient form of Christianity through their practice. Their name came from their ecstatic dancing (they were dubbed “Shaking Quakers” by outsiders), and they lived celibate lives in which gender roles were egalitarian.

The first Shakers in America were led by Mother Ann Lee, who sailed from England with eight followers in 1774. At the group’s peak in the mid-19th century, the Shakers in the United States had from 4,000 to upwards of 6,000 believers living and working in 19 communities.

Today, there are only two Shakers living in the sole community that remains active: Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in Maine. Many of the other Shaker villages have been converted into museums, the most famous of which is probably Hancock Shaker Village, with its iconic Round Stone Barn, in Massachusetts. The strictly celibate Shakers didn’t reproduce; they adopted children, and families would join as a group and conform to the Shaker way of life, with men and women living as brothers and sisters.

Design as Prayer and Practicality

If the term Shaker is widely known today, it’s due at least in part to the genius of the society’s design sensibility and craftsmanship. A case of drawers offered for sale at Sotheby’s in January 2019, for example, is almost heartbreakingly austere. Its proportions resemble those of an 18th-century American highboy, or chest-on-chest, but in the Shaker chest there are no rococo curves, no carved broken pediment at the top, no cabriole legs or decorative brass drawer pulls. Apart from the language and line of its form, it sports no ornament at all.

[For the Shakers], craft and design weren’t only an aesthetic pursuit, but a spiritual practice in which aesthetics made their beliefs tangible. They valued integrity, honesty, and frugality – all of which seemed to steer them away from anything that seemed unnecessary, like fussy ornamentation.

European modernism and minimalism inadvertently trained 20th- and 21st-century people to adore the directness and understatement of Shaker design, and taken together with the Shakers’ graceful craftsmanship, it’s no wonder that their furniture and objects command ever higher prices at auction. But for the Shakers themselves, craft and design weren’t only an aesthetic pursuit, but a spiritual practice in which aesthetics made their beliefs tangible. They valued integrity, honesty, and frugality – all of which seemed to steer them away from anything that seemed unnecessary, like fussy ornamentation.

The character of Shaker furniture can be read in these terms in particular, and also as a response to American design during the early decades of Shaker communities. According to Nicholas C. Vincent, a former research associate for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American Wing, the first generation of furniture makers in the communities were recent converts, and thus they knew the prevailing techniques and styles of American furniture from their previous employment.

“Already familiar with the prevailing neoclassical fashion for rectilinear and attenuated forms and restrained ornamentation, they took these impulses even further, eliminating veneers, inlays, and carving,” Vincent writes. “Shaker tenets held that manufactured goods should be honest in construction and appearance; therefore ‘deceitful’ practices such as veneering and applied ornamentation were incompatible with Shaker beliefs.” Shakers used local wood, eschewed imported or exotic hardwoods, and generally espoused the craftsman ideal of “truth to materials,” whether they were directly familiar with the writings of John Ruskin or not.

There were other aspects to the Shaker design ethic, too. Like most utopian communities, Shakers were farmers, and many of their innovations – from clothespins, circular saws, and flat brooms to the wheel-driven washing machine – were inspired by a desire to make their daily work more efficient.

Despite their emphasis on egalitarianism, there was a division of labor between men and women. Men tended to do much of the carpentry and blacksmithing, while women did the majority of the spinning, weaving, sewing, and crafting of “fancy goods” for sale, such as brushes and scented pillows. The Shaker Seed Company also sold seeds for edible and medicinal plants, and some Shakers sold high-quality homespun items.

The Oneida Community: From Free Love to Joint-Stock

The Oneida Community’s best-known material legacy, its silverware, is actually part of the story of its decline; the community had largely dispersed and ceased to practice its core beliefs by the time Oneida silverware was on the market. The group began as a religious utopian experiment in upstate New York, established by a preacher and antislavery activist named John Humphrey Noyes. Like the Shakers, Noyes was “millenarian,” in that he anticipated transformational change in the world. Noyes and his followers also believed that it was possible to live free of sin in this lifetime – a belief known as perfectionism.

The Oneida Community, now a mass-market brand of silverware, appropriated its name from the First Nations tribe whose homeland they eventually settled on in upstate New York. Noyes founded the utopian community in 1848, and for a few decades the group lived together, working four to six hours per day, living without personal possessions or money, and for a time, practicing “complex marriage.” Noyes, who was typically Victorian in his fascination with electricity and magnetism, believed that human sexuality had a kind of electric charge, and the community itself was akin to a battery. More love with more partners meant more holy energy and a greater chance of attaining immortality.

The Oneida story is unusual as tales of Victorian craft utopias go because the product for which the society is best known, the silverware that is still manufactured today (the brand is now owned by a major corporation) was made after community members abandoned the notion of complex marriage. In 1879, the community decided to reorganize its social arrangements and support itself in a more typically capitalist fashion. Couples paired off, and the commune was restructured as the Oneida Community, Limited – with shares apportioned according to each person’s initial capital investment in the community and how much work they had contributed to building it.

The Oneida Community’s best-known material legacy, its silverware, is actually part of the story of its decline.

Animal Traps, Canning, Thread – and Silverware

The new venture got off to a rocky start. None of the younger members had ever worked outside the community, and some had grown up never seeing money. They tried producing and selling animal traps under the trade name Victor; they manufactured thread, and had a canning business, too. Then one of John Humphrey Noyes’ children, Pierrepont, who had a leadership role in the newly formed company, decided that focusing on silverware was the only path to prosperity.

Pierrepont Noyes’ insight at the turn of the 20th century was that sterling silver (that is, flatware that’s made entirely of silver) could only reach a limited number of consumers because it was costly to buy. Silver-plated flatware was an accessible alternative. Oneida called this flatware Community Plate.

Like mass-market china and department-store furniture, Oneida Community Plate appealed to the growing population of middle-class Americans with refined tastes and an interest in entertaining. This population boomed after World War II. A print ad for Community Plate that ran in the mid-1940s (similar to the one shown at left) featured a bride and groom embracing against the backdrop of a Federal-style convex mirror complete with a patriotic eagle. It proclaimed that Oneida flatware – which came in patterns with names such as “Coronation” and “Lady Hamilton” – was “for keeps.”

Burning the Background

In this postwar, back-to-normalcy era, the modern Oneida company that descended from the community’s original joint-stock corporation, took pains to hide the sect’s unconventional past. In 1947, on the heels of a highly successful advertising campaign marketing Oneida flatware to returning GIs and their brides, the company burned a cache of papers, letters, and diaries that documented the practice of complex marriage.

In a story for Collectors Weekly, Ellen Wayland-Smith, a descendent of members of the community and the author of the 2016 book Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table, suggests that the destruction of the family papers may have been driven by an effort to conceal not just complex marriage, but a whole set of idiosyncratic practices, including the fact that Oneida children were sent to live in a communal children’s house at 3 years old, and that Oneida women did not present themselves like their counterparts outside the community. Instead, they wore unique garments that combined pantaloons with knee-length dresses, and they kept their hair very short. Their style made them a target for ridicule, and even violence, from neighbors. In her study of Victorian dress, Pantaloons & Power: A Nineteenth-Century Dress Reform in the United States, historian Gayle V. Fischer notes that women dressed in the Oneida fashion were attacked by mobs in incidents that occurred in Hartford, Connecticut, and in New York City’s Grand Central Station. The attacks had a chilling effect on the women’s desire to wear their distinctive clothing out in public, which finally led to the abandonment of the style altogether.

Wayland-Smith believes that because women of the Oneida Community had seemed unfeminine or androgynous by Victorian standards, they might have been off-putting to consumers in postwar America, many of whom were eagerly settling into highly stereotypical gender roles in matters of work, domesticity, and appearance.

Failures – and Legacies

The Oneida Community as it was originally conceived eventually failed, and the Shakers dwindled from thousands of members in the second half of the 19th-century to a mere two at Sabbathday Lake today. But is Shaker furniture a failure? Hardly. And what about Oneida silverware? Far from it. The work of Shaker craftspeople can still connect us to perennial values: functionality, simplicity, humility, elegance, and spiritual beauty. Community Plate made silverware accessible to American consumers who couldn’t afford sterling but wanted to set accessible to American consumers who couldn’t afford sterling but wanted to set an elegant table.

One community remained stalwart in its refusal to compromise; another made compromises that sometimes hurt, but nevertheless resulted in a thriving business and service to thousands. As Americans face a turbulent era in which we’re called upon to reflect on, critique, and change some of our most deeply held beliefs while preserving values that are under siege, the lessons these two traditions have to teach us about the necessity of both firmness and flexibility go well beyond the realm of craft.

Image Credits

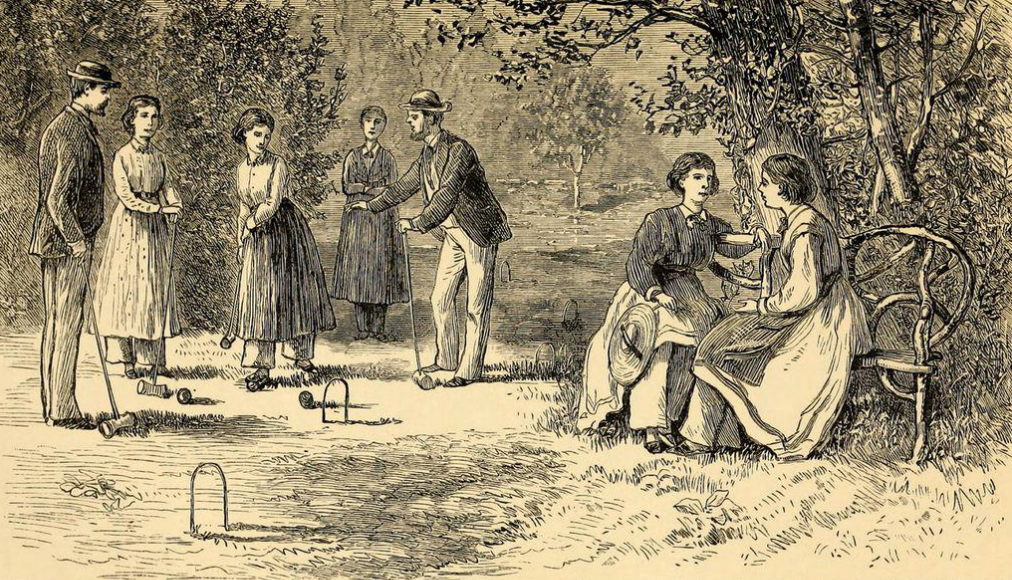

Oneida illustration: Charles Nordhoff, The Communistic Societies of the United States.

Stand photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1966.

Dancing illustration: Clara Endicott Sears, Gleanings from Old Shaker Journals, compiled by

Clara Endicott Sears, University of California Libraries.

Oneida Community members photo: Syracuse University Library, Department of Special Collections, Oneida Community Collection