Stephanie Syjuco

Pattern Recognition

As published in the Renwick Catalog, November, 2018

Antebellum South (Simplicity) (detail; see below)

What does it mean to be American? How do we look? What does it mean to look as though we belong? Nearly every endeavor Stephanie Syjuco undertakes is motivated by a question, and depends on the viewer to provide part of the answer, or to ask a question of themselves. Her work questions everything from notions of identity, to broader cultural and economic concerns, such as, what is the value of labor? Why are logos important to consumers? What makes an object counterfeit? She is fascinated by systems, so her work usually involves multiples in various forms, from off-the-rack clothing to crocheted knock-offs of luxury accessories and ersatz pieces of currency. Her projects tend to capture the friction that occurs where a standardized entity meets an individual (or many millions of individuals). Every person who views or interacts with one of Syjuco’s projects will experience it differently, depending on their own role in the larger global networks of fashion, consumerism, money, and labor. Running through each of her projects is an emphasis on context, and how we see things differently when the backdrop changes.

Syjuco’s inclusion in the 2018 Renwick Invitational may come as a surprise. When asked to comment on the meaning and significance of presenting her work at the Renwick for this exhibition, Syjuco wrote: “The fact that I am not a traditional craft artist but a visual artist interested in how shifting identities are fictionalized and play into the narrative of who is and who isn’t ‘American’ is really powerful for me. As someone included in a craft show, I claim the word ‘craft’ as a verb to manufacture a complicated and contradictory identity as an American.” (1) An installation artist with a strong interest in social practice projects, Syjuco is more apt to create a communal workspace or an elaborate mise-en-scène inside an exhibition space than a series of discrete objects on pedestals. She teaches in a university art department (at the University of California, Berkeley) and not in a craft or material studies program. She does not work closely with any of the well-known craft organizations — ceramics residency programs, woodturning centers, or glass studios — with which other Renwick Invitational artists are often involved. It’s fair to say that Syjuco exists parallel to the institutional craft ecosystem in America rather than within it. Since the craft world is accustomed to leading with material, it’s worth asking what Syjuco’s medium is — if other artists are devoted to glass or clay, batik, or even recycled film strips, we might say that Syjuco’s medium of choice is pattern.

Recently, Syjuco has created a series of works that use patterns found within systems, standards, and typologies. Craft artists — for lack of a much-needed better term — already engage in the types of systems and typologies Syjuco exploits. Today’s potters and weavers make their own versions of recognized forms using methods, technology, visual motifs, styles, and even modes of display that are known quantities both within their fields and far beyond. Pottery, for example, has its own instantly recognizable ancient Greek-inspired emoticon. (2) What makers communicate when they create something new is symbolic as much as it is aesthetic: an object can be understood, if nothing else, as an example of its type. Syjuco is exploring ways to apply this logic to her multidisciplinary practice. In her work, the categories and typologies we use to understand objects cannot be uncoupled from the way we categorize people. Thoughts on gender, race, nationality, and status — ways we identify ourselves and see others — are quite literally woven into the fabric of her projects.

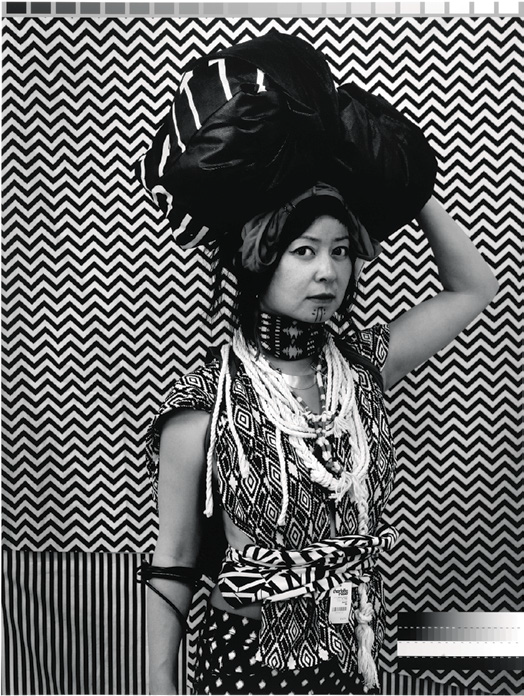

Cargo Cults asks the viewer to question their assumptions: What kind of exoticism are we viewing when we see a woman of color wearing “ethnically” styled clothing? That the clothing she chose to use is from twenty-first-century American retailers and made overseas — probably very far away, at that — underscores the notion of camouflage, and the disruption of our ability to situate and classify the subject being depicted.

To play with assumptions influenced by such typologies, Syjuco created her 2016 photographic series Cargo Cults, stemming from her earlier 2013 installation Cargo Cults: Object Agents (fig. 1). (3) She bought off-the-rack garments from mass- market retailers including Forever 21, H&M, American Apparel, Urban Outfitters, Target, the Gap, and others, and then styled them on herself to evoke the clothing depicted in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Western portraits of exotic subjects in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa (figs. 2 and 3). She posed against a black-and-white backdrop inspired by “dazzle camouflage,” a graphic technique that was used on battleships during World War I to confuse the aim of enemies. After the photographs were made, she returned all the garments to their retailers.

FIG. 1 – Cargo Cults: Object Agents, installation view, Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE, 2013

FIG. 2 – Cargo Cults: Head Bundle, 2016, archival pigment print. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Museum purchase

FIG. 3 – Cargo Cults: Java Bunny, 2016, archival pigment print. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Museum purchase

To explore other ways information and identities can be masked, Syjuco has been using the artistic possibilities of digital editing tools, like the special effect of chroma-key, used in film and video post-production to “drop out” a particular color range and transform a background. The effect is often used for weather newscasts, to make meteorologists appear in front of a computer-generated weather map, which is in reality just a blue or green screen, or to insert an actor into a digitally enhanced scene. Syjuco’s Chromakey Aftermath 2 (fig. 4) uses this concept to make a statement on how information can be edited or hidden from our view. It depicts a monochromatic green assemblage of the kinds of detritus that might be left after a protest — banners, poles, flags, clothing — all rendered in “drop-out” green, suggesting that the entire endeavor and its “props” have been digitally selected and deleted, perhaps from an imagined news broadcast.

FIG. 4 – Chromakey Aftermath 2 (Flags, Sticks, and Barriers), 2017, archival pigment print. Collection of the artist and courtesy RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Textiles and the needle trades have always been central to Syjuco’s practice, and by studying the history, social significance, and aesthetics of sewing patterns produced by companies like McCall’s and Simplicity (fig. 5), she found that in both the world of film production and in the domestic realm of sewing, people and objects can be rendered as “cutouts,” or stand-ins symbolizing a “type.” Inspired by this premise, Syjuco is working on fabric garments using what she calls “chromakey fabrics,” sewing recognizable period costumes in bright green (fig. 6). Visitors to historic sites like Independence Hall in Philadelphia, or the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, Virginia, will instantly recognize the tricorn hats, ruffled caps, and cloaks of the historical interpreters dressed in colonial garb. Different gowns, suits, bonnets, and hats could likewise signify Massachusetts pilgrims, people living in the Civil War era, or covered wagon pioneers. Those who grew up with American Girl dolls may even have biographies and narratives at the ready to flesh out the different archetypes. For future projects, Syjuco envisions introducing a twist to this constellation of recognizable cutouts by using boldly geometric, stereotypically “ethnic” patterned fabric as a visual backdrop for figures representing recognizable motifs of Americana, in a sense making the figures “green-screened” (but still visible) on a new, multicultural landscape.

FIG. 5 – Materials used for The Visible Invisible project

FIG. 6 – Left to right, The Visible Invisible: Plymouth Pilgrim (Simplicity), 2018, cotton muslin chromakey back- drop fabric, ribbon, lace, buttons, and display form; Antebellum South (Simplicity), 2018, cotton muslin chromakey back- drop fabric, polyester satin, crocheted cotton, ribbon, lace, buttons, and display form; Colonial Revolution (McCall’s), 2018, cotton muslin chromakey back- drop fabric, ribbon, lace, buttons, and display form. All collection of the artist

The pattern that spans the entirety of Total Transparency (Background Layer Bleed) (fig. 7) will be familiar to anyone who has worked with imaging software. The recognizable white-and-light-gray checkerboard indicates, in its most literal sense, neutrality: it stands in for a neutral background, the absence of image or pigment of any kind. In a more figurative sense, it signifies a work in progress. It means that a field of color, a pattern, or an image is about to be layered onto the surface. While Syjuco’s piece is decidedly analog, careful and close inspection reveals that the work is actually a quilt — each gray or white cotton square has been pieced together, forming a textile that spans thirteen by twenty-six feet (fig. 8). Metaphorically, the quilt is meant to blanket whatever it covers in a neutral, yet-to-be-determined sort of American-ness. First shown in her 2017 exhibition CITIZENS, it provided a backdrop for fabric banners (fig. 9) and anonymous portraits.

FIG. 7 – Total Transparency (Background Layer Bleed), 2017, hand-sewn quilting cotton. Collection of the artist and courtesy RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

FIG. 8 – Total Transparency (Background Layer Bleed) (reverse detail)

FIG. 9 – Ungovernable (Hoist) (foreground), 2017, sewn muslin and steel armatures. Collection of the artist and courtesy RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

The same pattern drapes over one of these portraits in Total Transparency Filter (Portrait of N) (fig. 10), suggesting a new way to consider the comfort and protection of a quilt. The young woman’s identity is totally obscured, but she is an undocumented American who was able to complete her college degree as a DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) recipient, which, as of this writing, has been terminated by the Trump administration and is under litigation. The pattern in the photograph echoes the dense “dazzle camouflage” graphics that Syjuco employs in Cargo Cults, but it is subtler and softer, even cozy. There is perhaps no textile as quintessentially American as a quilt. Thus, Syjuco’s checkerboard pattern is at once an absence, in the Photoshop sense, a digital non-entity waiting to be filled in at some later date (the subject’s fate and identity as an American unknown), and a historic presence, in the American textile sense, an heirloom that represents domestic tradition, skill, and national identity.

FIG. 10 – Total Transparency Filter (Portrait of N), 2017, archival digital print. Collection of the artist and courtesy RYAN LEE Gallery, New York

Syjuco’s 2016 project Neutral Calibration Studies (Ornament + Crime) (fig. 11) further questions notions of cultural and political identity. It takes the form of a classic still life, organized around color calibration charts, the kind that photographers use to determine which colors are “neutral” or “correct.” In the early to mid-twentieth century, in photography as in so many other aspects of visual culture, “neutral” was Caucasian. On a large platform, a cacophonous assemblage of objects and images compete for attention, many of them dating from the period of time in which colonialism was beginning to unravel and modernism was taking shape. Central Asian rug patterns downloaded from the Internet and blown up to appear pixelated hang above a reproduction of Freud’s office settee in Vienna (fig. 12). The French modernist designer Charlotte Perriand reclines on a chaise longue designed by Le Corbusier, and Man Ray’s photograph of a white model posed with an African mask is framed by faux potted plants. Other details, like a traditional Filipino rattan butterfly chair, are painted neutral gray, as is the entire back side of the installation (fig. 13). The question of what is “neutral” and what is “colorful” or “colored” is as loaded as it gets in contemporary America.

FIG. 11 – Neutral Calibration Studies (Ornament + Crime), 2016, wooden platform, neutral grey seamless backdrop paper, digital adhesive prints on laser-cut wooden props, dye-sublimation digital prints on fabric, items purchased on eBay and craigslist, photographic prints, artificial and live plants, and neutral calibrated gray paint. Collection of the artist and Nion McEvoy

FIG. 13 – Neutral Calibration Studies (Ornament + Crime) (reverse detail)

FIG. 12 – Neutral Calibration Studies (Ornament + Crime) (detail)

Syjuco’s use of pattern has a third effect, beyond the metaphorical and the aesthetic: her community-based projects often involve group crafting sessions, or she might invite visitors to an exhibition to participate in a work. For her 2008 Counterfeit Crochet Project, she created a website inviting people with crochet skills to create handmade faux designer handbags, like those made by the luxury houses of Chanel, Fendi, and Prada (fig. 14). The crocheters were instructed to search for low-resolution images of luxury bags online, then create a crocheted knock-off based on that image. Due to both the technique being used and the pixelation of the source image, the resulting “counterfeit” bags looked only faintly like their authentic counterparts (fig. 15). By working with volunteers, Syjuco was able to add a dimension of labor critique to a piece that addresses the production of fashion, both high and low. “Crochet is considered a lowly medium,” she writes, “and the limitations imposed by trying to create detail with yarn takes advantage of the individual maker’s ingenuity and problem-solving skills.” (4) In this work, the participation of others is as crucial to Syjuco’s piece as the materials themselves and the ideas they manifest.

FIG. 14 – The Counterfeit Crochet Project (Critique of a Political Economy), 2008, installation and participatory work- shop that traveled to Beijing, Istanbul, Manila, Milan, Berlin, Karlsruhe, Gothenburg, Los Angeles, New York, Milwaukee, Jönköping, and San Francisco

FIG. 15 – The Counterfeit Crochet Project (Critique of a Political Economy), 2008

Patterns can be found in the ways we understand our identity and nationhood, and how we see ourselves and each other in a country whose relatively short history is shaped by contradictory elements. Our national story includes cherished narratives of hand-sewn flags and hand-built log cabins, of military might and global dominance in manufacturing — and the painful ebb of that dominance as we struggle to pivot into an unknown future. With all of that in mind, and in the rich historical and contemporary context of the Renwick Gallery, an “American craft calibration study” is as timely as ever. Syjuco’s inclusion in this year’s Invitational expands the reconsideration of what American craft means — and who American craft artists are — furthering the Renwick’s exploration into the evolution of craft in the twenty-first century. SARAH ARCHER

Notes

1. Unless otherwise noted, quotes are by Stephanie Syjuco, taken from interviews conducted by the author, October 2017.

2. The Amphora emoticon ( 🏺) was introduced as part of Unicode 8.0 in 2015.

3. The term “cargo cult” refers to a phenomenon first noted in Melanesia, in which religious groups formed around the belief that material wealth can be obtained through ritual worship.

4. “The Counterfeit Crochet Project (Critique of a Political Economy),” Stephanie Syjuco (website), accessed March 28, 2018.