Designing Disneyland

A bountiful new visual history lays out the story behind the building of the Magic Kingdom

As published in Architectural Digest, November 22, 2018

When it opened in 1957, the Monsanto House of the Future measured 1,300 square feet (nearly 121 meters), consisted of 20 separate pieces of molded fiberglass, and sat on a 16-square-foot (about 1.5 meter) block of concrete, with utilities running through a central core. More than 20 million guests visited the forward-thinking experiment before its removal in 1967. Courtesy Disney Enterprises, Inc.

In the mid-1950s, when Walt Disney’s long-planned, eponymous California theme park was taking shape, he found himself butting heads with a member of the his construction crew. “One of the contractors on the job tried to substitute plastic for wrought iron, and Walt insisted on authenticity,” says Chris Nichols, whose new book Walt Disney’s Disneyland (Taschen, $60) lavishly illustrates the creative process of the park’s creation, from drawing board to ribbon-cutting. “Imagineer John Hench said that if the design elements were not authentic, guests would have a harder time suspending disbelief and placing themselves in the story,” Nichols tells AD PRO. That, in a nutshell, is what sets Disneyland apart from the scores of other amusement parks, fairs, and attractions that both presaged and followed its 1955 debut: No other park of its kind was designed with so much emphasis on the idea of transporting visitors, both physically and narratively, into another world, as though a teacup ride might actually sweep one down the rabbit hole and into Wonderland.

The original Disneyland sign on Harbor Boulevard welcomed guests from 1958 to 1989. Its bold colors, shapes, and kinetic exuberance make it an icon of midcentury design. Collection of Dave DeCaro, davelandweb.com

Nichols’s handsome tome presents a treasure trove of archival material, including drawings and photographs from the historical collections of The Walt Disney Company, that sheds light on how Disneyland came to be. Needless to say, it didn’t appear fully formed at the wave of a magic wand. Walt Disney initially conceived of the idea when he was visiting a Griffith Park merry-go-round with his school-age daughters and wondered if he could build a place where the attractions were as much fun for grown-ups as they were for children. For inspiration, he visited places like Henry Ford's museum and Greenfield Village in Michigan, as well as European pleasure gardens such as Denmark’s Tivoli and Efteling in the Netherlands. What he encountered over and over were distilled “experiences” that offered visitors a rich sensory taste of something else—fantasy, history, nostalgia, play—in a comfortable setting with plenty of creature comforts and variety.

Disney and artist Herb Ryman, who had worked on such films as Dumbo and The Wizard of Oz, spent a weekend together at the studio putting Walt’s ideas on paper. “Herbie, this is my dream,” the artist remembered Walt telling him tearfully. “I’ve wanted this for years and I need your help. You’re the only one who can do it.” (art, Herb Ryman, 1953) Copyright © 2018 Disney Enterprises, Inc.

In designing Disneyland, Walt Disney created something like a permanent world’s fair, but it was more than that, according to Nichols. He notes: “In one of Walt's early descriptions of the park, he said, ‘We hope it will be unlike any other place on this earth: a fair, an amusement park, an exhibition, a city from Arabian nights, a metropolis from the future.’ So there are elements of a world's fair, but Disneyland goes far beyond a fair.” The experience of Disneyland would be more cinematic. “By combining the fantasy of familiar characters, the ornate landscaping and wide walkways that direct guests so artfully, the high quality control in materials and attention to storytelling both through attractions and architecturally, Disneyland transcends the fair,” Nichols says. In other words, Disneyland wasn’t simply a series of attractions clustered together in a convenient area, it was aesthetically engineered down to the last detail, with the goal of setting a richly atmospheric scene around every corner.

Walt Disney described his park on television in 1954. Copyright © 2018 Disney Enterprises, Inc.

And this makes perfect sense when you consider its origin story: Disneyland was brought to life through television. With his ideal theme park in mind, Disney initially thought the project would take shape as a tourist attraction next to his animation studios in Burbank, California, but ultimately decided there wasn’t enough room there, and that the studios themselves didn’t have that much to offer visitors. Instead, he approached ABC about creating a show called Disneyland, in exchange for which the network would provide funding to build the real thing. Construction began in the summer of 1954, and the finished park was unveiled on ABC during a live press event in July 1955. Disney’s own lifespan (1901–1966) encapsulated the great leaps of the 20th century. He personally experienced the shift from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles, followed by one innovation after another: airplanes, space flight, movies and television, early computers, plastic, and atomic energy. Disney’s own parents grew up during the gilded age (indeed, his father worked at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893) and “the future,” from his perspective, was the space age.

One of the original members of the WED model shop, Harriet Burns, helped construct the scale models for Pirates of the Caribbean so that Disney could study every detail from the point of view of guests riding the finished attraction. Though Disney oversaw the construction of the attraction, it did not open until about a year after his death in 1966. Copyright © 2018 Disney Enterprises, Inc.

In 1955, when Disneyland opened, it comprised a series of “lands.” Some capture the look and feel of an imagined past, like Frontierland, which evokes the Old West, and Main Street, U.S.A., which is inspired by a turn of the 20th-century Midwestern town, in which the use of forced perspective makes the reduced-scale buildings appear larger than they really are. Others offered visions of the future, like Tomorrowland, for which real NASA scientists, including Wernher von Braun, Willy Ley, and Heinz Haber offered technical advice. Key attractions in 1955 included the Aluminum Hall of Fame, the Hall of Chemistry, the TWA Moonliner, and Autopia—a very 20th-century, car-centric vision of “tomorrow.”

Fourteen years before actual astronauts would visit the Moon, the Rocket to the Moon and Astro-Jets attractions offered Tomorrowland guests the simulated thrill of blasting into space. Courtesy Disney Enterprises, Inc.

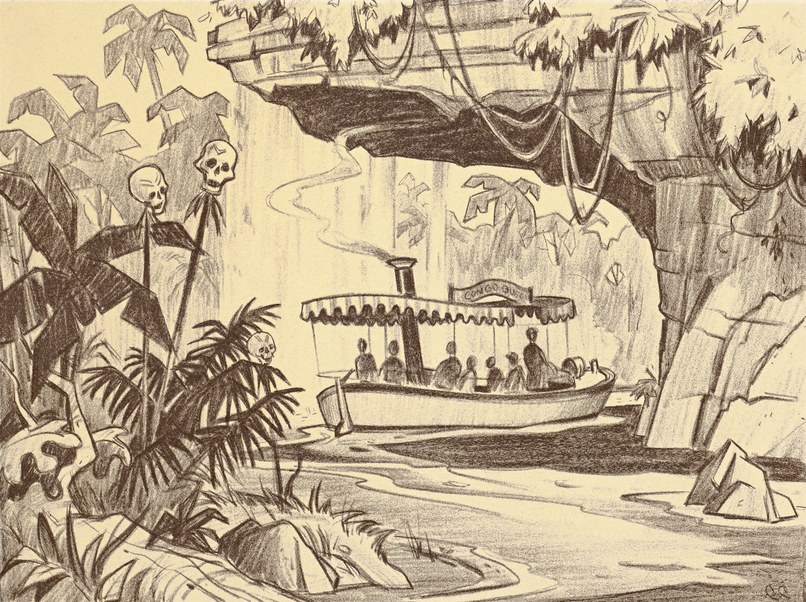

Adventureland captured the exotic draw of the postwar tiki craze and was designed with Asian and African jungles in mind. Decorated with carvings, masks, drums, and architecture inspired by the South Pacific, its initial attractions included the Jungle Cruise and the Enchanted Tiki Room. And Fantasyland, which is home to the iconic Sleeping Beauty Castle, captures the fairy-tale legends and characters most associated with Disney movies: Peter Pan, Alice in Wonderland, Pinocchio, Snow White, and, of course, Dumbo the Flying Elephant.

The rare experience of seeing the “backside of water” while the riverboat meanders under the Schweitzer Falls is a highlight of the Jungle Cruise, consistent with Disney’s goal to create the “wonder world of nature’s own realm.” (art, Collin Campbell, 1954 ) Copyright © 2018 Disney Enterprises, Inc.

One of the great pleasures of Nichols's book is poring over the drawings and sketches that mapped out the lands of Disneyland when its physical site in Anaheim, California, was still an orange grove, because they demonstrate the kind of cohesive, all-encompassing vision that was needed to produce something like Disneyland. It wasn’t enough to capture the flashy, colorful carnival atmosphere of a typical amusement park. Nor did Disney wish to emulate the cluster of pavilions that drew visitors to world’s fairs, demonstrating cars of the future, or the fashion designs of foreign countries, or new household appliances.

The Monorail was the first of its kind in the Western Hemisphere and was intended as a realistic preview of transportation in tomorrow’s cities. One of the designers of the Monorail, John Hench, said the modes of transportation at Disneyland not only needed to look good in appearance but also be “a pleasure to watch in action.” (art, Bob Gurr and John Hench, circa 1959) Copyright © 2018 Disney Enterprises, Inc.

Disneyland was the first theme park that combined the physical experience of visiting an attraction with the immersive experience of being taken on a journey, as a film or television show would do. Tomorrowland, in particular, captured the optimism of its moment, with its cheery combination of educational exhibits and Googie-influenced architecture. At its 1955 inauguration, Disney described Tomorrowland’s attractions as “a living blueprint of our future.” “Tomorrow,” he said, “can be a wonderful age."